Review of Empire Falls, Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Richard Russo

Miles

Roby is Everyman, or at least every middle-aged person. Well, at least he would

be if all of us were as honest about his or her motives as Miles is about his.

For me, Miles Roby’s thoughts and emotions were the most compelling aspect of

Richard Russo’s Empire Falls. Who

among us has not wrestled with finding fulfillment in life, choosing how to

treat difficult people, cowering under and climbing over weighty fears, trying

to understand our family members’ choices, piecing together childhood

flashbacks, sorting through others’ expectations of us? Russo has crafted a

story that certainly inspires contemplation of the motivational strength of

good and evil, love and hate.

The

story in Empire Falls spans three

generations, although present action takes place in just a short period of

months. For all Miles Roby’s introspection and Empire Falls’ small-town

simplicity, the story also contains a fair amount of action, some violent.

Forty-two-year-old Miles manages the Empire Grill, and most main characters have

a long history with the town of Empire Falls, so the story weaves long-standing

and new conflicts with comfortable, candid friendships as Miles confronts his

seemingly impossible dreams. Conflicts

and friendships are among family members, among Miles’ high school friends, and

with Francine Whiting, the wealthy woman who “owns” the town and whose mantra

is “power and control.”

This

is a book you will not just read—you will experience. The hair on the back of

your neck will prickle when edgy Jimmy Minty enters a scene. You’ll prickle,

plus hold your breath, when his menacing son Zack walks onstage. You might want

to shake Max until he develops a conscience; you’ll certainly marvel at Miles’ loving

patience with him. You’d like to grab a cup of coffee and sit down with Father

Mark. Sometimes you’ll pity Janine; other times you’ll wash your hands of her. You’ll

want to put protective arms around Miles’ and Janine’s teen daughter Tick, just

as Miles longs to. You’ll root for Miles and his yearnings. These and other

characters are so well-wrought, you’ll live their scenes right along with them.

A

few miscellaneous comments … I think this story could have been told with much

less crude profanity. I like the undercurrent of Miles’ faith as anchor,

comfort, and source of wisdom. And I love Russo’s signature wry humor. Here’s

just one example: “For Miles, one of the great mysteries of marriage was that

you had to actually say things before you realized they were wrong.” I like how

Miles perseveres to find life in an economically depressed town and how he

chooses people and kindness over more alluring pursuits. I like the cerebral

nature of this book; Miles thinks through his relational dilemmas and has a pivotal

epiphany—with Russo revealing Miles’ ponderings all along the way. And I like

how Russo explores Miles’ relationship with his mother. Although she died long

ago, she is ever present in Miles’ life, not just as a shaper of his character.

It is a mystery of her life that Miles must solve in order to surmount his

fears. Russo is a master storyteller of interpersonal relationships, and I

highly recommend this Pulitzer-Prize-winning novel.

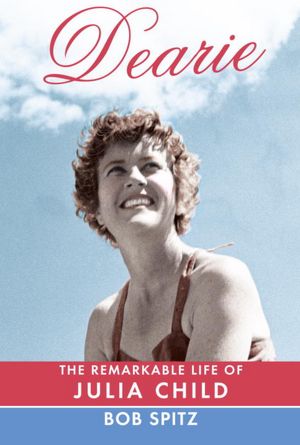

How

many books about Julia Child can a person thoroughly enjoy? Three, it turns

out. Having read Noel Riley Fitch’s biography, Appetite for Life, and Julia Child’s and Alex Prud’homme’s My Life in France, I wondered if Bob

Spitz’s Dearie: The Remarkable Life of Julia Child might prove to be too much of

the same. It did not. Though time line events were familiar, behind-the-scenes

anecdotes and interviews were new.

How

many books about Julia Child can a person thoroughly enjoy? Three, it turns

out. Having read Noel Riley Fitch’s biography, Appetite for Life, and Julia Child’s and Alex Prud’homme’s My Life in France, I wondered if Bob

Spitz’s Dearie: The Remarkable Life of Julia Child might prove to be too much of

the same. It did not. Though time line events were familiar, behind-the-scenes

anecdotes and interviews were new.