Such a sweet story ~ Arthur Moses, Maddy Harris, and Lucille

Howard finding each other, taking care of each other. We all should be so

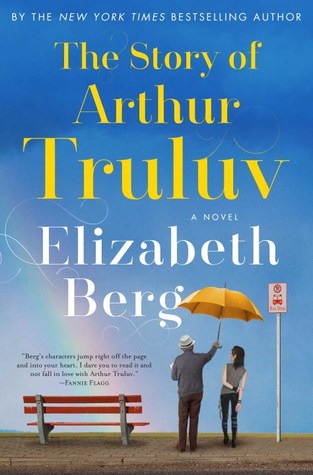

blessed. Author Elizabeth Berg’s novel, The

Story of Arthur Truluv, is based in the unpleasant facts that life can be

cruel, some people find cruelty entertaining, and loss and longing are

profoundly painful. Berg then transforms these lonely sorrows into hope.

Such a sweet story ~ Arthur Moses, Maddy Harris, and Lucille

Howard finding each other, taking care of each other. We all should be so

blessed. Author Elizabeth Berg’s novel, The

Story of Arthur Truluv, is based in the unpleasant facts that life can be

cruel, some people find cruelty entertaining, and loss and longing are

profoundly painful. Berg then transforms these lonely sorrows into hope.

Eighty-five-year-old Arthur Moses’ beloved wife Nola dies six

months before this novel opens at her grave, with Arthur having his daily lunch

with her. Maddy Harris, still painfully alone in the world after her mother’s

death and father’s distance, hangs out at the cemetery to avoid her high school

classmates’ contempt. Arthur and Maddy strike up a conversation. Meanwhile,

Arthur’s next-door neighbor, Lucille, is distraught and depressed at losing her

recently reappeared high school beau. Despite their differences, these three

people extend simple kindnesses to each other. Friendships are born. Lifesaving

friendships. Life-enriching friendships. Second-chance-giving friendships.

I enjoyed reading this uplifting novel. Plus, I always enjoy

Elizabeth Berg’s presentation of everyday life. A bonus in The Story of Arthur Truluv happens in the symbolic cemetery. A

favorite pastime of Arthur is imagining lives of buried persons from minimal

facts on headstones. What he comes up with is classic Berg. For example: “When

she read, she liked to be barefoot and she liked to lace her fingers through

her toes.” [p. 48] Another excerpt: “Even in old age, he and his wife would

load up the car with blankets and lawn chairs and go out to reserve a place in

the park while the sky was still a smoky red and the birds had not yet begun to

sing.” [p. 49] I very much admire Elizabeth Berg’s creative combination of her

powers of observation and imagination.